31 January marked the 30th anniversary of the implementation of Britains seat belt law. A television interviewer sent to quiz me about my opposition to the law said I reminded him of Hiroo Onoda, the Japanese soldier who spent 30 years in the jungle, fighting on, unaware that the war had been lost. The interview was not broadcast; I assume that when he got back to the office his boss decided that after 30 years the story was no longer newsworthy.

I have actually been in the jungle for more that 30 years. In 1981 I produced a paper entitled The Efficacy of Seat Belt Legislation (published in 1982 by the Society of Automotive Engineers). The paper earned me a gratifying number of column inches in the Hansard report of the 1981 Parliamentary debate that resulted in the passage of the law that was finally implemented in January 1983. The column inches were reasonably equally divided between those who were persuaded by my evidence and those who werent.

The debate was introduced by Conservative MP Ivan Lawrence whose opposition to the law was essentially libertarian. But he welcomed my evidence that the law would not save lives.

Mr. Lawrence This is one of those subjects which stir feelings deeply and genuinely, regardless of party politics. It touches upon freedom, and all of us have been sent to this place to protect, as far as we might, the individual liberties of our constituents against the remorseless hunger of a State and bureaucratic machine trying to gobble it up. .. we now have some solid evidence that we have never had before. In earlier debates we have heard talk of some figures from Australia that were airily waved about as supporting the compulsion case, but we were never given any statistics from the many other countries experiencing compulsion. Now we have just that. We have a comparative study of road fatality statistics in no fewer than 18 countries, covering about 80 per cent of the world’s car population.

Examining the national statistics which have not been available earlier, Mr. John Adams of University College, London, in January this year published his findings.

Mr. Austin Mitchell (Grimsby) The only one that the hon. and learned Gentleman can dredge up.

Mr. Lawrence It is a darned sight more than anything that has ever been dredged up by the arguers for compulsion on the Opposition Benches, who have never presented this House with a comprehensive analysis of the statistics.

Mr. Mitchell rose

Mr. Lawrence I hope that the hon. Gentleman will be able to catch your eye later, Mr. Speaker. However, I am conscious that many hon. Members wish to speak. Therefore, I hope that the hon. Gentleman will forgive me if I continue.

Mr. Mitchell rose

Mr. Lawrence Mr. John Adams of University College, London, compared Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Holland, Norway, Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, Israel, Australia and New Zealandall countries with a compulsory seat belt law that is enforcedwith Italy, the United States of America, Japan and Great Britain, where there is either no compulsory seat belt law or it is not enforced.

Mr. Adams’ findings are astonishing and unexpected. Although most of the countries experienced a substantial decrease in road accident fatalities in the years following the 1973 oil crisis, the decrease was greater in those countries without a compulsory seat belt law than in those countries with one.

Mr Mitchell rose

Mr. Lawrence The hon. Gentleman will have to carry on

Mr. Deputy Speaker (Mr. Bernard Weatherill) Order. The hon. and learned Gentleman is not giving way.

Mr. Mitchell I wondered whether the hon. and learned Gentleman was giving way.

Mr. Lawrence The hon. Gentleman can carry oil wondering. I should like to complete my case. The promise of massive reductions in the number of deaths because of compulsion simply has not materialised. There is no evidence to show that seat belt compulsiontaking accidents overallsaves lives; nor does it reduce the overall number of injuries. However, the inherent unreliability of comparative statistics makes any positive conclusion about injuries impossible.

That survey has put the cat among the pigeons. Those who have stood up publicly for compulsion have some understandable reluctance to stand on their heads in public, whatever the evidence may be. Others, less publicly committed, will want to stop and reconsider the matter. The first attack made on Mr. Adams’ inconvenient findings was that he had not substantiated his tentative hypothesis that the reason why there seemed to he no reduction in the death rate, and probably an increase after compulsion, was that protecting car occupants from the consequences of bad driving encourages bad driving. As a rock climber may take more risks when wearing a harness, so a car driver may do so. That attack was irrelevant. Mr. Adams was only describing the statistics. He did not set out to explain them and still less to prove an explanation. It is for all of us to consider why those statistics produce that astonishing result. However, it is beyond argument that they produce it.

The next attack came from Lord Nugent, who proposed the amendment in the other place. On 11 Juneonly six weeks agohe said that Mr. Adams’ mistake was to muddle up pedestrians, cyclists, motor cyclists and so on with the only relevant victimsdrivers and front seat passengers. I hear notes of assent and support for that criticism from Opposition Members.

Mr. George Foulkes (South Ayrshire) Nonsense!

Mr. Lawrence I hope that we shall hear some constructive speeches from Opposition Members, rather than “Nonsense!”

Lord Nugent’s criticism of Mr. Adams was patent rubbish since the survey and its appendix contained three graphs, giving information about car occupant fatalities in Sweden and in seven EEC countries. Nevertheless, the criticism was repeated by Dr. Murray MacKay in a letter to The Times on 11 June. Mr. Adams replied, pointing out the error of his critics in The Times in a letter of 16 June. That seems to have made no difference. Once some people have made up their minds, they will not change them, whatever the facts.

On 26 June, the motoring correspondent of The Times repeated the error. Once again, the patient Mr. Adams drew the attention of The Times to the error and once again, the correction was ignored. The leader in The Times stated: Dr. Adams fails to distinguish sufficiently between all road user casualties and those among car occupants.

Mr. Austin Mitchell rose

Mr. Lawrence Mr. Adams has produced 57 graphs. He concludes: Nowhere in all this data can there be found any evidence of the enormous beneficial effect promised by the advocates of legislation. On the contrary the data persistently suggests that the effect of the legislation, if there is one, is perverse. There, for the moment, the evidence rests.

Now, more than 30 years on, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents has issued a press release to celebrate the implementation of the law and to celebrate the role of Lord Nugent (their then president) in its passage. The press release also adds to the patent rubbish of which Ivan Lawrence complained:

31 January 2013

ACTION STILL NEEDED TO SAVE LIVES 30 YEARS AFTER SEATBELT LAW, WARNS RoSPA

Greater compliance with seatbelt legislation could help save lives in road crashes says RoSPA, as it marks the 30th anniversary of the law coming into force.

Well over 60,000 lives have been saved by seatbelts since January 31, 1983, when the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents then-President, Lord Nugent of Guildford, won the day for compulsory wearing in the front seat of cars by introducing an amendment to the Transport Bill in the House of Lords. A law making it compulsory to wear seatbelts in the back of cars was introduced in 1991.

RoSPA is shameless. On the 20th anniversary of the law they claimed it had saved 50,000 lives. On the 25th anniversary they claimed 60,000 or 2400 lives a year. Now, on the 30th anniversary, using the scientific method called hand-waving extrapolation they claim well over 60,000.

The nonsense of RoSPAs 60,000 claim was exposed in a number of postings at the time of the 25th anniversary. It was a claim also made in a Department for Transport press release and in a press release by PACTS (the Parliamentary Advisory Council on Transport Safety). The 25th anniversary claims can still be found on the DfT and PACTS websites. PACTS was especially proud of it contribution to the achievement:

On the 31st January 2008, the 25th anniversary of the law change which made front seatbelt wearing compulsory was celebrated. PACTS itself was set up by Barry Sheerman MP as part of the fight to get mandatory seatbelt wearing turned into legislation. Eight years later it became compulsory for all backseat passengers to use seatbelts and it is estimated that since the introduction of the first law change in 1983, seatbelts have prevented 60,000 deaths and over 670,000 serious injuries.

Intriguingly, a few months after this press release four prominent road safety experts who describe themselves as being among the leadership of the Pacts Richard Allsop, Oliver Carsten, Andrew Evans, and Robert Gifford published an article in Significance, a journal of the Royal Statistical Society, in which they advanced a much more modest claim for the number of lives saved by the seat belt law: not 2400 per year but 164.

Also intriguingly, for the first time of which I am aware, serious, statistically-qualified, advocates of seat-belt legislation acknowledged a risk transfer effect:

The clear reduction in death and injury to car occupants is appreciably offset by extra deaths among pedestrians and cyclists.

and

the best estimates from both the analyses summarised here are that extra deaths to vulnerable road users did accompany the introduction of mandatory wearing of seat belts.

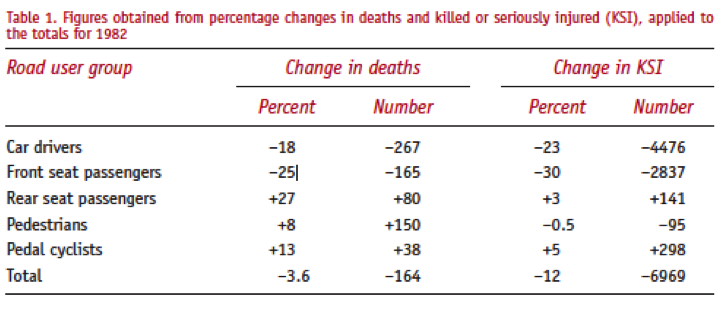

Table 1 from Allsop et al summarizes the risk transfer effect for vulnerable road users cyclists, pedestrians and rear sear passengers who were not covered by the seat belt law.

The seat belt law, they explained, has

two potential unintended effects. First, the affected group may have more collisions, perhaps through taking greater risks, realizing that the likely consequences of collision have been reduced. Second, there may be an increased risk to other road users not protected by the safety measure. In these ways, the reduction in death and injury in the protected group may be partly offset by extra death and injury caused to others.

Dedicated readers of this website will recognize that these two unintended consequences are what for some decades I have been calling the risk compensation effect.

Allsop et al went on to observe that

Whether belts are worn by choice or by law, these unintended effects could lead to the number of deaths to belted car occupants falling by less than the amount one would expect if they were unbelted, and to extra death and injury among pedestrians, cyclists and unbelted occupants. This applies equally to legislating for belt-wearing and to simply encouraging it: it should rule out neither, but be taken into account when considering either.

For 30 years the common response to this argument has been that of David Ennals (above), a supporter of the law, who referred in the parliamentary debate to the extraordinary argument by Dr. John Adams of University College, London that the wearing of seat belts could lead to a false sense of complacency. He went on to assert that the hypothesis is that ˜protecting an occupant from the consequences of bad driving encourages bad driving, adding there is no evidence of that. He went on to thank RoSPA for producing evidence that proved me wrong yes RoSPA and I go back a long way.

RoSPA never got round to publishing the evidence. Mine passed peer review and was published in the Transactions of the Society of Automotive Engineers as The efficacy of seat belt legislation.

Other comments on my paper made during the debate will convey the flavour

- that [Adams]piece of research was, as I have said before, bogus.

- the so-called new evidence of Mr. Adams.

- Mr. John Adams is a lecturer in geography.

- He has produced an eccentric paper and has made the preposterous suggestion that the wearing of seat belts encourages people to drive more dangerously.

- Is it seriously argued that safety devices make people behave more dangerously? I think that the majority of people would consider that a ludicrous proposition.

- Those of us who have attempted to look at the problem seriously find the evidence in Dr. Adams’s paper highly spurious and bogus.

- Professor Adams’s thesis is unproven. It is new.

Lord Nugent does indeed deserve much of the credit that RoSPA bestows upon him for the passage of the law. Shortly before the debate he sent a letter on behalf of RoSPA to every MP stating:

Dr Adams has recently published a paper advancing the thesis that wearing seat belts may actually increase road accidents by encouraging a false sense of security. His paper requires detailed analysis with the aid of much background information from the countries concerned before authoritative comment can be made upon it. RoSPA and the Transport and Road Research Laboratory are undertaking these studies, meantime it is relevant to record that Dr Adams does unequivocally state that wearing seatbelts greatly improves the chance of avoiding injury.

The immediate objection to the letter that I made at the time was that it was disingenuous. I had stated that seat belts improve a car occupants chances of avoiding an injury in a crash. The fact that fatalities and injuries, to occupants and others, had not fallen with the implementation of the law was my principal evidence for risk compensation.

A second objection can now be raised. After 30 years, the results of the RoSPA studies commissioned by Lord Nugent have yet to be published, nor has its preposterous contention that the seat belt law is saving 2400 lives a year been justified.

While RoSPAs contribution to the seat belt debate over the last three decades can be dismissed as hand-waving statistical nonsense, the argument of Allsop et al deserves further consideration, if only because its authors have established track records as serious transport safety researchers

Despite having accepted that lives of vulnerable road users have been lost as a result of the seat belt law 268 according to their Table 1 they still argue that seat belt laws should be retained because they save more lives 432 car occupants than they cost. Here is their justification for keeping a law that by their estimation kills 268 vulnerable road users a year

road safety is made up of many individual safety measures and equity among road user groups across road safety policy as a whole in no way implies that each individual safety measure should in itself benefit all road user groups equitably. Nor does each road safety measure necessarily act only to reduce death and injury: many measures reduce aggregate death and injury by reducing them in incidents of certain kinds by more than they increase them in other kinds. A case in point is installing central barriers on motorways. These prevent many deaths and injuries by preventing errant vehicles on one carriageway crossing onto the other and then having very injurious head-on collisions.

But there are some incidents in which injury or death result from a vehicle striking the barrier and bouncing back onto its own carriageway when the opposing carriageway was fortuitously clear of traffic; had there been no barrier, there would have been no injuries. That is no reason to do away with motorway barriers. The barrier is justified when the deaths and injuries prevented outweigh appreciably the extra deaths and injuries that result from its presence.

It would therefore be a severe constraint on the use of safety measures if any measure were to be ruled out for which the larger number of deaths and injuries saved were differently distributed among road user groups from the smaller number resulting from the measurethe more so because most of us at different times belong to different user groups.

The wearing of seat belts is therefore not exceptional among safety measures in that extra deaths and injuries that may arise from wearing occur in part (only in part because, if wearers drive more riskily, some of the extra deaths and injuries will occur to vehicle occupants) to different road user groups than those among which deaths and injuries are preventedthough the difference is perhaps sharper for belt wearing than for many other measures

Any increase in death and injury to pedestrians and cyclists that stems from wearing of seat belts should be borne in mind in the formulation of road safety policy as a whole and contribute to prioritising safety measures benefitting pedestrians and cyclists. But so long as wearing of belts saves substantially more death and injury among vehicle occupants than the increase among pedestrians and cyclists, the latter does not rule out the provision and wearing of belts. Nor, therefore, does it rule out laws requiring the wearing of belts.

When I first encountered this sophistry (both seat belts and central barriers are measures designed to protect vehicle occupants) justifying the killing of the vulnerable to save the lives of the best protected I put it to one of the authors, Rob Gifford, that the same argument would justify an organ harvester lottery:

In the light of that argument I would welcome your comment on this analogy: an Organ Harvester Lottery in which healthy people will be selected at random (not unlike road accidents) to donate organs to people in need of them. One heart and one liver could save two lives at the cost of one slightly better than the ratio that you argue justifies keeping the seat belt law. Throw in two kidneys and you get a four to one ratio of lives saved to lives lost. This is a gruesome but not wholly inappropriate analogy given the myth circulating at the time (and still) that the success of the seat law was responsible for increasing the shortage of donor organs.

I have yet to receive a challenge from the PACTS authors to the appropriateness of this analogy.

Let us conclude with an examination of the appropriateness of the analogy comparing me to Hiroo Onoda with which we began. According to this analogy my war against seat belt laws was lost over thirty years ago with the passage of Britains first seat belt law.

In one sense the war has indeed been lost. The myth of the efficacy of seat belts and seat belt laws is now so deeply entrenched that it appears to be immune to evidence. It is routinely advanced in support of other safety regulation, such as compulsory cycle helmets, as an example of the efficacy of measures that compel people to be safer than they voluntarily choose to be.

An acceptance of the myth leads to its routine insertion into all sorts of other arguments. I offer a recent example from the New York Times an article by a Cambridge philosopher, Huw Price, explaining why he was working to establish in Cambridge the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (C.S.E.R.).

His project he likens to a societal seat belt. He elaborates the analogy:

our fate is in the hands, if thats the word, of what might charitably be called a very large and poorly organized committee collectively short-sighted, if not actually reckless, but responsible for guiding our fast-moving vehicle through some hazardous and yet completely unfamiliar terrain.

and

Second, remember that all the children all of them are in the back. We thrill-seeking grandparents may have little to lose, but shouldnt we be encouraging the kids to buckle up?

A fact not widely known to those who might be persuaded by this analogy is that, when Britain passed a law in 1989 requiring children in back seats to belt up, the number of children killed in back seats increased (see Risk, pp 126-127). My provisional explanation, pending a more convincing one: when the children were secure in their government approved safety harnesses, parents reverted to their customary, vigorous, style of braking, cornering, and accelerating.

So common is the deployment of the efficacious-seat-belt analogy that I, for peace of mind, have learned, to let it pass. But in this case, sensitised by the impending 30th anniversary celebrations, I ventured a comment.

The myth of the efficacy of seat belt legislation

Why should the belief in the efficacy of the law have persisted for so long in the face of so much evidence that it hasnt worked? Myth has been called “ideology in narrative form”.

The narrative. Before the passage of the law in 1981 there had been numerous parliamentary debates about a seat belt law. Over this period the evidence, and popular support, appeared to grow stronger. Experiments with crash test dummies provided convincing graphic evidence of the protection afforded by seat belts in crashes. And in the early 1970s all the Australian states passed seat belt laws that appeared to arrest a long established rising trend of road accident deaths. The belief in the potential road safety legislation to save lives gained momentum.

By the time of the 1981 debate the law had acquired a large number of influential champions practically any organisation with an interest in road safety including the British Medical Association, the Royal society for the Prevention of Accidents, the Royal College of Surgeons, the Royal College of Nursing, the Society of Automotive Manufacturers and Traders, and the Automobile Association. Lord Avebury offered this list in a House of Lords debate as compelling evidence for legislation: Why, he asked, would all these institutions seek to mislead the public?

But none of these organisations, and none of the countries that followed the lead of Australia, produced any compelling evidence that legislation had saved lives. They all cited the original, misconstrued, Australian evidence, or other people citing the Australian evidence, or other people citing other people citing the Australian evidence.

Ever since, the champions of the law have felt free to assert its effectiveness with impunity. Five years ago I pointed out to the Department for Transport, the Parliamentary Council for Transport Safety and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents that their 25th Anniversary claim that the law had saved 60,000 lives was preposterous. But the claim can still be found on their websites. Echoing Lord Averbury one might well ask, why would these institutions seek to mislead the public?